Is time like the river? There are

places where it feels less like a flow, with one age succeeding another, than

an accumulation of all ages together.

Witness the Oxford Plain. Through an agrarian

spread of yellows and greens the river ribbons blue. Here upstream of

Wallingford it bends, and in that bend is a tiny village which, at first glance,

might as well be any other.

Dorchester-on-Thames, not to be confused with its

better-known namesake the provincial capital of Dorset, is a tiny settlement of

1,000 people. Little houses. Sheep in fields. Aside from a peculiarly large church, what

is there to set it out in the shadows of the vast structures of power and

privilege that line this valley?

Look closer.

|

| Are those not some noteworthy earthworks (at right)? And where are these views coming from on the flat Oxford Plain? |

|

| Hill forts. How about it then. |

In fact this subtle riverbend is one

of the richest historical treasure-troves in the Thames valley. Six millennia

of continuous human habitation are written in the shape of its landscape, from

the ramparts and ditches everywhere you look to the coins, bones and grave

goods that practically erupt from its gravel. It took the English some time

to realise it. They’d wrecked much of it through gravel quarrying by the time

that they did. But once they did, the Dorchester bend became one of the most prized archaeological zones in the country.

These are deep memories it harbours. Most

of them long precede the English nation. They precede even its precursors. They

go all the way back to a time when far, far away, Gilgamesh and the Egyptian

pyramids were happening; and when here on the very fringes of the story of

humanity, the migrants who wandered out this way got out their flint hand-axes

and, for the first time, whacked down the stakes of this

island-peninsula’s earliest permanent settlements.

|

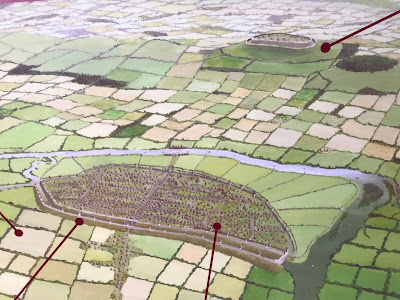

| A landscape in time, not just in space. The shape of this land is the product – and continuation – of the stories of about six settlements that succeeded each other on and around the Dorchester bend. |

Doubtless life in these earliest

societies to put down roots here would have been full of struggles. But had it

yet gone so fundamentally wrong as we find it today? Was this then, as it is

now, a land of abuse? Had the masculine power fantasy, which should never have

existed, been invented yet? Whatever diseases afflicted them, was it in

them yet to come up with such staggering political and cultural mis-reactions

as they have for COVID-19 today?

And because this is the middle

Thames, we have to ask: what of their forts? The Iron Age fort on the hill, and

fort in the bend; the Roman fort just beneath where the village is now: were

these, already, Privilege Forts? Or were these forts for everyone?

There’s simply too much in the way to

answer these questions now. Nonetheless, let’s take a few steps into a

landscape where perhaps there’s less to impede those ancestors’ touch on your

skin than anywhere else in this part of the country.

Start: Wallingford Bridge (nearest

station: Cholsey – ten minutes by bus, or take the X39 or X40 from Reading for

approx. thirty minutes)

End: Confluence with River Thame, near

Dorchester-on-Thames (nearest station: miles away, take the X39 or X40 bus

to Reading or Oxford instead)

Length: 8km/5 miles

Location: Oxfordshire – South

Oxfordshire

Topics: Wallingford Castle Meadows, Benson,

Shillingford, and thousands of years of settlement at Dorchester-on-Thames

Wallingford Castle Meadows

Dorchester is only a couple of hours’

walking upstream of Wallingford, beginning with what was formerly the grassy

envelope of Wallingford castle.

|

| The river from Wallingford Bridge, with The Boat House pub and boat rental at left. |

|

| Wallingford natives take their morning coffees and relaxations by the river. |

|

| Almost immediately the riverbank greens, with open fields appearing inland. |

|

| The fields are Wallingford Castle Meadows – a wide strip of pastures between the river and the embankment where once towered the castle’s outer wall. |

These fields were likely an

integrated part of the castle complex, so have inherited the names King’s

Meadows and Queen’s Arbour. It is thought they grew hay to feed its

animals while offering an extra layer of wet and marshy defence. Recent archaeology

has unearthed a chalk foundation for a stone outbuilding here,

perhaps a dock or a quay.

|

| After the castle’s demolition the hay meadows were reseeded and chemically treated to suit commercial dairy cows. This ruined their biodiversity, so now they are trying to bring it back through better management. These fellows’ summer grazing appears part of that plan. |

|

| Nuuo. |

|

| The meadows stretch on past the northern limit of the castle ruins. |

From here farmland takes over for the

short stretch to the commuter village of Benson.

|

| The vessels moored along here appear barely lived in, when not outright haunted. |

|

| Much of today’s reach is free of habitation, giving the river a chance to present its more natural face. |

|

| By this point we are more or less clear of the chalk hills. North and west of Wallingford it’s all farmland. |

Benson

Eventually a weir comes in sight,

heralding the village of Benson. The towpath switches to the north bank

here, though rejoining it once across requires a quick circumnavigation of

Benson’s waterside housing.

|

| The weir is attached to Benson Lock. |

|

| These are so common a sight now as to almost cease to warrant commentary. |

|

| Benson Lock is another installed by the Thames Navigation Commission in the 1780s, replacing an earlier flash-lock attached to a fourteenth-century millers’ weir. |

|

| Unusually you can walk atop this lock and weir to cross the river. |

Benson is a residential village and

travellers’ outpost perched on gravel in otherwise marshy surroundings. It was

known as Bensington until a century or two ago, by when they seem to have

found the extra syllable too much effort.

Benson shares in some recurring

themes of this region’s heritage. It has evidence of thousands of years of

human activity, as well as a frontier position that got it fought over in

generations of conflicts: between the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, between Matilda and Stephen, and between the Royalists and

Parliamentarians in the Civil War. It later flourished in the service of

stagecoach journeys on the London-to-Oxford road, and keeps busy doing the same

for river travellers today with its large boatyard, bungalow park and

waterfront café.

|

| The riverside at Benson, with pleasure-craft lined up a long way up the quay and large crowds bustling through the café. |

Benson’s other landmark is its Royal

Air Force (RAF) base, built to its east at the beginning of World War II.

Originally installed to train air crews and house fighters and light

reconnaissance craft, it now appears concerned with the trimmed-down air

force’s support helicopters and transportation.

|

| The path out of Benson passes this complex of holiday cabins, likely aimed at people on long boat journeys. |

|

| Then it’s straight back into rurality. But the fields here are not quite as remote as they seem. Across them runs the A4074 which became the main Reading-to-Oxford road in the 1980s, replacing the route through the Goring Gap. |

|

| A more old-fashioned instance of local river traffic. |

While the north bank proceeds through

fields and woods, the south is occupied by the grounds of an old manor house

known as Rush Court. The original house was thoroughly rebuilt in the 1920s and

has since been turned into a residential care home.

|

| The wall of Rush Court’s ornamental gardens is visible from across the river. |

|

| Summer draws to a close. A long and bitter winter lies in store for this land. |

|

| A lighter vessel lingers about the walled Rush Court grounds. |

|

| Indeed, the flowers here have increasingly had their say for this year. |

In due course another small hamlet

crops up by the river.

Shillingford

As its name suggests, Shillingford

is defined by its river crossing, which since 1827 has taken the form of one of

the Thames’s prettier stone bridges. It is the latest in a line of bridges

going back at least to the fourteenth century and preceded in turn by fords

and/or ferries.

|

| The cabins on the waterfront here look perilously vulnerable to flooding. |

|

| Shillingford Bridge. The origin of Shilling in this case is unclear, though most likely refers to someone’s name. |

Shillingford has long connected

important land routes on both sides of the river. Thus its service as a

crossing point is thought to be extremely old – at least as old as the Roman

road system, but probably much older.

For some reason the towpath now

spends some time on the opposite bank before rejoining this one, and there is

no route here along the Shillingford bend. The wayfarer is thus frustrated into

a short detour into the village, and less pleasantly, along the busy Reading-to-Oxford

road.

|

| Fearsome clusters ambush those who dare walk the narrow path behind Shillingford’s houses. |

|

| The English do enjoy their walls and fences. This alleyway is an exhibition of several different types. |

|

| This is a much-used road with poor air, narrow pavements, and long waits for anyone trying to cross it. |

Eventually a path offers

passage back to the river, and from there, at last, entry into the

time-twisting landscape of the Dorchester bend.

|

| Another of these lurks in the meadow that leads back to the river. |

|

| The final approach to Dorchester is a straightforward march across this field. |

Dorchester-on-Thames

We now tread on ground that’s

experienced more than six thousand years of continuous human settlement, and

whose very shape has shifted in its recording.

Two geographical features stand out on this riverbend, and in so doing have set the parameters of human activity here.

We encounter the first as we reach a bridge not over the Thames, but over a

tributary which joins it here after its own long journey: the Thame.

|

| The confluence of the Thames and the Thame. |

|

| The Thame looks barely navigable, but it’s a major tributary with serious geographical and cultural significance. |

Witness the extreme resemblance of

the names. Thames has been interpreted as ‘dark river’ in this land’s old Celtic languages,

and though the Thame (which unlike the larger river, they pronounce to rhyme

with game) possibly shares this origin, the truth of it is lost in the

fog of prehistory. Such is frequently the way with rivers, which are there all

the way through, often bring people in in the first place, and so tend to carry

the most ancient names of all.

The Thame rises in the Vale of

Aylesbury, an eastward extension of the Oxford Basin whose Late Jurassic clay

dominates the neighbouring province of Buckinghamshire. By flowing south into

the Thames just as the latter emerges from its own southward curve, the pair create

a peninsula and pack it with gravelly alluvium. Like that they have provided a

relatively stable, accessible and defensible seat for settlement in an

otherwise marshy area.

It is significant that from this

point on the Thames is referred to in the Oxford English dialect by a different

name: the Isis. It would be tempting to dismiss this as a posh scholarly

affectation on that university city’s part if not for how the practice’s weight,

enhanced through its use by Oxford’s fearsome rowing subculture, has prevailed

on cartographers like the Ordnance Survey to label it River Thames or Isis

from here on up on official maps. In fact the name Isa first emerges in

writing in the fourteenth century; there is a theory – perhaps put forward by

Oxford academics at that time, and almost certainly erroneous – that the Roman

name for the Thames, Tamesis, was the outcome of this merger here,

linguistic as physical: Thame plus Isis.

|

| Present-day Dorchester adjoins the Thame on this peninsula. Most of its preceding settlements did too. |

|

| South across the river, the region’s other defining feature is at once apparent. |

On the south side the land rises into

a pair of hills that offer the only high ground on this level floodplain. This

is an orphaned outcrop of the Chalk Group, which offers sweeping views across

miles of surrounding landscape. This huge defensive, navigational and

aesthetic value has garnered these hills many names. They are the Sinodun Hills

(thought to be from Celtic: ‘old fort’); the Wittenham Clumps (which

strictly speaking refers to the beech woods on their summits); the Berkshire

Bubs (a reminder that ancestral Berkshire encompassed this bank till 1974);

or more colloquially, thanks to a sixteenth-century lady of the local manor who

by this estimation cannot have been small, Mother Dunch’s Buttocks.

That aesthetic value is also sought

by today’s recreational walkers, who climb them for some of the best views in

the region.

|

| Back downriver the roofs of Benson are in plain sight. From here there is a much clearer view of its RAF base with its hangars and airfield. |

Perhaps that combination is why this

area has been a magnet for migrating humans as far back as the Palaeolithic or Old

Stone Age. From this vast period – considered to span from the first ice-age

immigrations around 400,000 years ago, to the gradual warming of this land in

the last few millennia BCE – Dorchester’s gravel has yielded an impressive

number of worked flint hand-axes. This signature artifact of those times was an

indispensable tool for chopping and carving all manner of meats, skins, bones,

woods and other everyday materials.

A decisive transition marks the

Neolithic or New Stone Age, from around 4000 BCE: namely, that these nomads began to

cultivate plants and domesticate animals. It was this farming that rooted them

to fixed locations, offered food surpluses when things went well, supported

larger populations, and thus gave rise to more complex societies which

rearranged the environment around them. It was a momentous change – and the

challenge in any assessment of it is that it was precisely the pivot which underpins the settled cultures that carry on in the present day. Thus any evidence

about it, still fragmentary at best, is necessarily filtered through both the

curses and celebrations which the humans of today direct, often with fierce

conviction and the gravest of personal stakes, at their current ways of life.

Life for these early farmers was

probably neither the cesspit of sickly, bloodthirsty misery that the fans of

modernity – that is, its minority of privileged beneficiaries – please to

condemn them to for the contrast, nor an idealised golden age free of the raft of

horrors that modernity has largely amplified rather than created from scratch. What

then do we really know about these ancient people? To answer that we have to

look at the evidence they have left us, such as the pottery, earthworks and

burial sites that survive from that period. Of these, Dorchester’s promised to

be some of the most revealing in all of England – at least until that clever

and enlightened modernity got it in its head to lay waste to it by digging it

up for gravel.

Around the 1920s and 30s, when the

advent of powered flight offered new views of this land from the air, passing pilots

began to notice cropmarks in the farm fields north of the

present village. Cropmarks are patterns in plant growth which indicate altered

soil conditions beneath – such as caused, for example, by buried ditches or

wall foundations, to whose presence they serve as a clue.

Eventually these came to the

attention of the archaeologists. What they found was astonishing: an entire

Neolithic complex of ritual monuments and burial enclosures, spanning the

period 2-3,000 BCE. They then spent the rest of the century in a race against

the construction industry to rescue what they could from the gravel diggers

and, later on, the builders of the Oxford Road’s Dorchester Bypass.

|

| Cropmarks made by what came to be known as the ‘Big Rings’ ritual complex, as photographed from an aircraft by Major George Allen in 1938. It’s now that lake in the previous photo. |

Most of the enclosures contained

cremated human remains, sometimes with animal bones, arrowheads, or flint or

pottery fragments. Amidst them stretched the site’s largest structure by

far: a long, linear pair of ditches called a cursus, which ran roughly

where the Dorchester Bypass runs now and whose function remains unknown. Possibly

it was a boundary, a ceremonial route, or an axis of ritual alignment, very likely

with reference to the river. And next to this cursus had stood an outstanding monument:

the ‘Big Rings’ henge (as in Stonehenge) that made such an impression on

passing pilots. Centuries of farming had obliterated everything above the

surface, but the ditches beneath suggested a considerable double-ring of

standing stones or timbers.

We can scarcely guess at the

functions of sites like these, least of all when a nation’s response to such

precious evidence is to annihilate all trace of it in the pursuit of passing material

gain. Yet they do permit some general suppositions. For one, Stone Age humans

were not the grunting cavemen of popular imagination but sophisticated

communities which crafted skill-intensive tools and, far from being consumed by

material drives, re-shaped their environments, often at enormous expense in resources

and organised labour, to express abstract cultural pursuits and better understand

the patterns of nature.

It’s also interesting how what’s now

a largely peripheral belt of fields between Oxford and Reading seems to have

been a core of human activity from at least the third millennium BCE. It’s

easily imaginable that at least as many people would have been involved in

building and operating these monuments as live in Dorchester today. Perhaps we

could have learnt a lot more about them had their successors, in all the

advanced wisdom of their modernity, not, you know, mined their entire site to

oblivion.

Excavations of some of the later

sites here found bronze tools and ornaments, indicating the shift to what they

call the Bronze Age. This is considered to have lasted till about 1,100 BCE in

this land, but despite the use of bronze metal (and thus a rise in lasting evidence

in the form of bronze tools, grave goods and ceremonial offerings), Neolithic

ways of life are thought to have more or less persisted.

A more substantial shift came with

the use of iron, with the associated Iron Age in this land lasting through the final

millennium BCE. By that point settlements and populations were growing, robust political identities had emerged, and large ritual

monuments were falling out of fashion. The change is dramatically recorded in

the Dorchester landscape because it was now that a hillfort appeared atop the

Wittenham Clumps.

By then the Dorchester bend ran

through an overlap between three groups of people: the Atrebates on the

lower Thames to the south; the Dobunni in the upper Thames and Cotswolds

to the northwest; and the Catuvellauni about the Chilterns to the east.

These were Celtic or Belgic societies, but we know them today largely through

their Latinised names and accounts by the Romans who later subjugated them.

Little about their relationships over

these centuries is certain, although by the Roman arrival they were clearly

organised polities which appointed kings, minted coins, and traded far and

wide. How exactly this hillfort figured into their interactions is thus largely

a matter of conjecture, save that it’s easy to imagine its formidable

defensibility and prestige as a place of occupation. Although it has never been

excavated, several studies including a Time Team investigation have dug

up enclosed sites and rubbish pits in the surrounding area. Far from an

isolated outpost, it’s more likely it formed the nucleus of an interconnected

settlement system that engaged as much in trading, crafting and administration of

the surrounding communities as in military activity.

|

| The commanding view to the south, with the rampart running through in the foreground. |

|

| The other clump, on Round Hill, is the oldest set of planted hilltop beech trees in England at over three hundred years old. |

|

| Bovine custodians graze the rounds of the Wittenham Clumps as they prowl for human troublemakers. Witness them contemplating action against these on account of their barking dog. |

The hillfort seems to have fallen out

of use towards the end of the millennium. Why is not clear. Perhaps the

politics grew stabler, and visual prestige and defence became less important

than trade and ready access. The outcome in any case is that the focus of

settlement shifted back across the river, this time to the very bottom of the

loop between the Thames and the Thame.

This rampart, known today as the Dyke

Hills, is believed to have formed the northern perimeter of a

forty-six-hectare town – significantly larger than the four-hectare hillfort –

that grew up here shortly before the Romans arrived. No less than one of

pre-Roman Britain’s first true towns (an oppidum in archaeological

parlance), its status as a major trading centre is attested by its profusion of

cropmarks indicating large houses and smaller enclosures – most likely

workshops and storehouses – arranged along organised roads, as well as the huge

concentrations of Iron Age coins that have sprung from its earth at the touch

of farmers’ ploughs.

|

| The ditch beneath the Dyke Hills rampart connected the Thames and Thame and would have surrounded the settlement with water, creating a defensible and well-connected island. |

|

| A peacock butterfly occupies the path, grumbling about countries that place greed for profit and property above the protection of precious heritage. |

This would have been the situation on

this bend when the Romans arrived in the first century CE. They integrated this

land into their empire as the province of Britannia, co-opting its Iron

Age peoples – by force, persuasion, or trickery as the case may be – and

gradually transforming their ways of life under Roman cultural practices.

Logically the name of Dorchester

ought to have its origins in this period. The -chester name element is

common in later Anglo-Saxon place names as a reference to fortified Roman

sites, though what the Dor signifies here is unclear. Excavations have

indeed revealed a Roman fort by the Thame just north of the Dyke Hills

settlement, where it would have controlled both the rivers and the Calleva

Atrebatum (Silchester)-Alchester route on the conquest-enabling Roman road

system.

Whether this caused the abandonment

of the Dyke Hills settlement, or whether its activity was already shifting to

what became the Roman civilian settlement that replaced the fort after its

demolition around 78 CE, is not known for sure. What is clearer is that this

was the first settlement on the site of the present-day village, and so has

influenced all further siting decisions to the present day.

If this was one of Roman Britannia’s tiniest

walled civilian towns, its small size did not detract from its importance. Swathes

of impressive finds have burst from the ground over centuries of village

activity, including high-quality glass, ceramic and silver goods such as jars

and cutlery; evidence of high-standard construction such as tiled roofs, mosaic

floors, tessellated pavements and decorated wall plaster; and the considerable

leavings of the farms, pottery kilns and cemeteries that sprawled across the surrounding

area. These, on top of the great effort they patently went to to protect this

town, suggest its crucial role as an administrative outpost and distribution

hub, most likely for this region’s rich agricultural produce.

These discoveries extend over the

later years of Roman rule, thus also helping to inform us about one of this

land’s most complex and psychologically sensitive periods: the long transition

from the declining Roman political and cultural systems, to those of the

Anglo-Saxon immigrants – the latter often spoken of, casually and inaccurately,

as the identity-fount of modern English whiteness.

On this too Dorchester offers a more complicated

picture. For instance, graves have been found of individuals of Germanic origin,

sometimes with Roman grave goods, or items from Gaul or the Rhineland, or in

some cases both. There is a good chance that these were continental mercenaries

(foederati), whom the sub-Roman people of this island were known to

invite in for protection as the Roman army departed. Though signs of Saxon

building and burial practices increase in the subsequent centuries, here as

elsewhere the evidence is of a long and multi-dimensional shift, for much of

which groups with different identities were living in close contact with one another. The quality of some of these finds suggests a persisting level

of wealth in sub-Roman/early Saxon Dorchester, and thus a continuing regional

importance for this town.

|

| These days another of these World War II pillboxes, unusually made of brick, guards the southern approach to Dorchester. |

The consolidation of the Anglo-Saxon immigrants

into settled kingdoms placed Dorchester yet again on a frontier zone. This time

it was the young kingdom of Wessex which looked across the river at the

great northern heavyweights of the period, Mercia and Northumbria

– the last time, incidentally, when the main power on this island was in the

north.

Dorchester’s status received a major

raise in this period. In 635 BCE, as recorded by the Northumbrian historian

Bede, a Frankish missionary called Birinus arrived, sent by

the Pope to convert the West Saxons to Christianity. Dorchester was significant

enough that it was here that Birinus presided over the baptism of Wessex’s

king, Cynegils, ahead of the latter’s daughter’s political marriage to the

already-Christianised king of the Northumbrians, Oswald. As part of the

arrangement Birinus was made the first Bishop of Wessex, and given land in and

around Dorchester to establish his cathedral.

In other words, Dorchester was suddenly the central religious headquarters of a newly-converted kingdom. Its new church

would in time evolve into its present one, while Birinus’s own name would later

be revived and exalted as the regional founder-figure for English Christianity.

For all this religion however, the

deeper significance of these events was political. In Dorchester the nascent

Wessex kingdom now had an anchor for its expansion north into the Thames

valley, as well as a platform for managing its interactions with its stronger,

more established rivals beyond it. The latter’s advantage was proven when

Dorchester subsequently fell under Mercian control. Its status as an

ecclesiastical centre was taken off it in favour of Mercia’s own more central

bishops of Leicester and Lindsey (Lincoln), and it didn’t get it back till

Mercia was devastated by the Scandinavian Vikings some two centuries later,

opening the way for the rise of Wessex under Alfred, the Viking defeat, and the

partition of not-yet-England into Saxon and Viking realms.

By that point however the rise of Alfred’s burhs at Oxford above and Wallingford

below suggested that beyond its status as a religious centre, Dorchester’s

commercial and strategic situation was in decline. This was confirmed when

after the Norman conquest of 1066 that ecclesiastical status was removed to

Lincoln yet again, this time for good. Nonetheless as an outpost of the

Lincoln bishopric Dorchester remained productive, sufficiently so that around

1140, on the site of the Saxon cathedral, the Bishop of Lincoln commissioned a monastery

whose main building dominates the local landscape to this day: Dorchester

Abbey.

|

| A close-up view of the Norman abbey, within whose structure traces of masonry from the Saxon cathedral are said to survive. |

|

| Unlike many English churches nowadays this one’s usually open, and actively welcomes visitors to poke around inside as much for historical interest as Christian observance. |

The Abbey was settled by monks from

an independent branch of the Augustinian order called the Arrouaisians, who

migrated in from across the Channel. Arriving as they did some decades after

the Norman conquest, they missed out on its wholesale land-grabs and so got

little in the way of manorial estates with resources and income. Instead they

made do with spiritual taxes and fees, and gradually accumulated holdings up the

Thame watershed in the centuries that followed.

|

| The building survives from this period, though has received many upgrades and renovations over the millennium. This window for example contains a mix of medieval and Victorian glass. |

|

| Another of the Abbey’s original pieces: the Norman lead font from around 1170, carved with figures of the Apostles from Christian mythology. |

Dorchester’s monks were pensioned

off, apparently in compliance, when Henry VIII and Thomas Cromwell crushed the

monasteries in the 1530s. Much of the complex was lost as a result, but

Dorchester Abbey’s main building was saved when it was bought by Richard

Beaufort, a rich local farmer, and returned to the community as the ordinary

parish church it still serves as today. It also escaped the worst of the next

round of obliterations, that wrought by the iconoclastic Puritans during and

after the Civil Wars. Despite being expensive to maintain it received some

dedicated restoration under the Victorian boom in interest in gothic

architecture, and stands on today as one of England's better-preserved large Norman monastic

pieces.

Dorchester’s national impact has since

declined, perhaps to a quieter level than ever in its history. Left as a

largely unremarkable farming village, its fields were Enclosed under a small

number of families like Beaufort’s with its agricultural base backed up by

milling and smithing. The village more or less fed and serviced itself,

sprouting local shops as well as numerous inns and pubs; the latter straggled

out of Dorchester’s old tradition as a road and river waypoint but got a brief

boost in the era of barges and turnpikes. By around the late eighteenth century

however the village became notorious for its poverty, and struggled to support

its victims of agricultural depression against the cruelty of that era’s Poor

Laws – the antecedent to the present Conservative Party’s abuse of the welfare

system to torture and punish people for being poor.

It’s easy to overlook this tiny settlement

in the apparent middle of nowhere. Enter its landscape with senses open,

however, and they quickly fill with a depth of heritage totally belied by its

settlement’s present-day humility. It presents a human story that runs unbroken

all the way back through Saxon immigrants, Roman occupiers, Iron and Bronze Age

traders and crafters; all the way back, indeed, to those prehistoric hunter-gatherers who came together and, for the first time in this land, took up the way

of the settler which, for good or for ill, the English carry on today.

Okay, admittedly for some quite

abominable ill. From the fount of settlement, not inevitably but by choice, has

arguably come the cult of property and a catastrophically murderous hostility

to anyone it deems unfitting: that is, nomads, wanderers, refugees, homeless people, and every indigenous

society they wrecked when they carried their settlement practices over the

sea. In a further irony, it was also from the way of the settler’s most

triumphant expression – cities – and their defining material, concrete, that

came the hunger for gravel which has done the most, on the Dorchester bend, to

destroy the very six-millennia-long story from which it emerged.

Nonetheless it is writ in this floodplain still.

You don’t have to dig through books or archives to read of it. Only walk,

instead – up the hills, along the ramparts, through and around the Abbey – and

you'll know it through your soles.

That’s the other irony. Here you best

learn the story of settlement by doing that which all settlers had to do first, yet too often come to despise when others do it too. You move. You migrate.

Very special thanks to the Dorchester

Abbey Museum for informing much of the content in this section, and for its

efforts to ensure a safe visit in COVID-19 conditions.

For those interested, a more detailed

overview of Dorchester’s story – with lots of photographs and diagrams – can be

found in Dorchester

Through the Ages by Jean Cook and Trevor Rowley (eds.), published by Oxford

University Department for External Studies in 1985.

No comments:

Post a Comment