The travelling poet Matsuo Bashō, setting eyes on Matsushima, was

apparently so overcome by what he saw that it left him speechless. In

an apocryphal but now immortal haiku, he could only remark:

Matsushima, ah!

A-ah, Matsushima ah!

Matsushima, ah!

Writing in Oku no Hosomichi,

he described it as 'the most beautiful spot in the whole country of

Japan...Tall islands point to the sky and level ones prostrate

themselves before the surges of water. Islands are piled above

islands, and islands are joined to islands, so that they look exactly

like parents caressing their children or walking with them arm in

arm. The pines are of the freshest green and their branches are

curved in exquisite lines, bent by the wind constantly blowing

through them...My pen strove in vain to equal this superb creation of

divine artifice.'

And Bashō was not alone in this

view. Matsushima, whose bay sits just up the coast from Sendai, is

established in canon as one of the Three Views of Japan, along with

the Itsukushima Shrine gate opposite Hiroshima and Kyoto's Amanohashidate sandbar of pines.

There are in all about 260

islands in the bay. Their shapes and sizes vary; some are close

enough to the coast that you can cross a bridge and walk on them,

while others are further out and can only be seen by boat. All seem

to grow from the same geological blueprint, however: a banded, bare

sedimentary base of rock, with a thick and sturdy green haircut of

pines on top.

This landscape's origins carry a

mysterious air; one study

at least suggests a massive landslide about 6,000 years ago. Indeed,

Matsushima's curious topography seems to extend inland: my day of

trekking in the area brought me in contact with plenty of cliffs,

slopes and woods who share the islands' pines and patterns of rocks

and caves.

What might have caused such a

drastic landslide? It's not hard to guess.

This region, like most of the

coastline it sits on, was battered by the earthquake and tsunami of

March 2011. The islands protected Matsushima bay itself from most of

the onslaught, only to pay a high price themselves. Take a look at

the before-and-after photo above: the book shows the scene (mirrored)

from before the disaster, and behind it, what's left of it after.

The surrounding districts fared

worse: towns were almost entirely inundated, and ships were hurled

inland by alarming distances. Though this vicinity of Sendai seems

well on the way to recovery, you still can't go far without finding

evidence of just what scale of destruction struck this place.

Even Date Masamune was given cause for consternation. The red

'tsunami line' on the pillar, just outside his museum, shows how high

the water rose here – and this at a fair way in from the coast,

behind the islands' protection.

As the mega-landslide hypothesis

echoes, this region is no stranger to violent upheavals of the Earth.

The Sendai Plain sits right on top of an active fault line, and March

2011 was far from the first time an earthquake-tsunami double blow

has brought it devastation. Indeed, in the year 869 C.E., official

records tell of a magnitude 8.6 quake and resulting tsunami which

ploughed its way 4 kilometres inland, flooding an area very similar

to last year's disaster and destroying the town of Tagajō, then the

regional capital. (Appallingly, Tagajō's modern incarnation was

again brought misery by the 2011 reprise, which killed almost 200 of

its citizens.)

After all the human dimensions of Tōhoku's story, the creation and

destruction, and the ways they connect in the Japanese tale as a

whole, these happenings suggest that what lies beneath them is more

fundamental still. The Earth and the sea – their power, their

untameable will – define the Sendai region, creating marvels like

Matsushima so celebrated all over the country just as it smashes them

all apart when humanity is not prepared.

And this seems a lens on Japan as

a whole: a nation defined, perhaps more than any other which today

calls itself 'developed', by the relationship between humans and

their living planet. Sometimes humanity here may struggle to accept

it: its flaws in adaptability to the quakes and tsunamis as old as

the islands themselves; the reckless nuclear games and reliance on

fossil fuels for energy; and the notorious industrial pollutions and

poisonings of the last century-and-a-half. Sometimes they understand

it a lot better: reflected in the animistic depth of Shinto

spirituality, or the strong organic themes suffusing so much of what

Japan creates, from its architecture and painted art, to its

literature (such as Bashō), to its national imagery, to more modern

expressions like video games and anime (where the creations of Studio

Ghibli must stand paramount among examples). However much the

political labels change – through all the ups and downs of history

– this alone is constant.

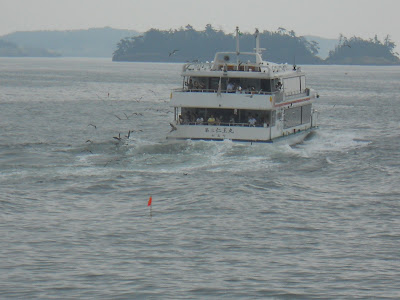

Sometimes it lets you visualize

it in funny ways. Taking a boat ride across the bay, for example,

will quickly bring you to the attention of these personable fellows.

They will see fit to descend on

your ferry in huge flocks and escort you all the way out into the

bay. They are not as aggressive as those I've encountered elsewhere,

and will surely be pleased if you give them something to eat. Who

remembers The Wind Waker?

Of the islands accessible from

the coast, one, Oshima (雄島),

is closed off: the bridge is gone, and I think we can guess what

caused it. A second, however, is right next to the boat pier: Godaido

(五大堂)

houses one of Masamune's worship halls (his own reconstruction this

time). The bridge was designed with gaps like that on purpose: it is

meant to get you centred, so your mind is concentrated by the time

you reach the hall.

Though I'm not one to worship

anybody – for I see everyone as equal, gods included, and the best

they can look for from me is friendship – I decided to give it a go

properly, rather than walk on the easy planks they've put there for

tourists. It was tricky in heavy hiking boots, but I somehow managed

to cross both ways without stumbling. Someone at least found this

funny.

Then there's Fukūrajima (福浦島),

the largest island in reach of the shore, connected by this handsome

252-metre red bridge.

This one's a thriving nature

reserve, where you can easily spend half a day scrambling around its

undergrowth, soft peat paths or headlands with magnificent views

across the bay. It also holds a number of beaches, and a rich

inhabitation of striking and very vocal insect life.

The town itself is somewhat

touristy, and makes the most of its reputation for local seafood –

eel (ウナギ)

seems especially popular. But it is worth exploration. Some rigorous

hiking gets you to the tops of its mountains, where you can see

across much of the bay, and better camera skills might convey how

breathtaking that in fact is.

One

of these mountains is Saigyō Modoshi no Matsu (西行戻しの松),

or “the pine tree that caused Saigyō

to go back home”. These rocks memorialize the story by which

Saigyō,

a high priest, met a young monk under a pine tree, and got into a

lively debate about the principles of Zen Buddhism. Finding himself

with no choice but to concede the debate, and feeling awed and

disgraced by the young monk's astonishing intellect, Saigyō

could no longer bring himself to go on to Matsushima and hastened

back home.

There

are also some more discreet local rarities you can find if you poke

around. These glassworks are the creation of the Japanese glass

master, Fujita Kyōhei (藤田喬平).

And in the centre, the temple

district, most of which was built or rebuilt by Date Masamune and

connects in various ways to his family – including the mausoleums

of his wife, daughter and grandson. The caves go back to the Kamakura

Period (1185-1333 C.E.), and for many centuries were used for

meditation or holding ashes.

This two-week voyage through the

north concluded – how else? – with an earthquake in the middle of

my last night in Sendai. It was time to head back to Tokyo with my

haul of treasure, and prepare for the battles with the academic

establishment to come.

In the month of August, 2012, I

travelled north and found a story more distinct, more overwhelming,

than I was prepared for; and found that at times, to walk on Hokkaido

at all is to walk through that story's pages in person. What can be

said, to look back on so momentous a range of places, people and

journeys – a northern mosaic, of which each piece I found only the

time to glimpse? How to encapsulate in conclusion these tales and

themes which ten accounts, each from a day or two of impressions,

could barely scratch at the surface?

Perhaps we should end with those

whose story it was to begin with – the Ainu.

When all is said and done, the Hokkaido story was theirs, and to

bring it to where it is now involved derailing it – much like the

European colonialists derailed the destinies of so many human

continents. This was cruel: the engine of Hokkaido's colonization ran

on a fuel of ethnic and cultural prejudice, and prejudice is always bad and brings our species into disrepute. The Ainu civilization has suffered to the

extreme as a result, and one can only hope that its gradual

resurgence today will one day, however long it takes, restore it to

the pride of place it deserves.

I have to believe it could have

worked out: because Hokkaido is a large island, with plenty of space

and resources for everybody, the perfect setting for a cooperative

journey. What might an Ainu city have looked like? Giant owls atop

skyscrapers? Bears wandering in the streets and parks, for whom you

have to brake when they cross the road? What of its energy sources?

Its political leadership? Its transport infrastructure? Its

festivals? How might their culture have blended with that which came

from Japan and from abroad, and how much stronger the outcomes have

been, if only the Ainu had been given the chance to join in that

blend as equals?

We can't be sure, of course: the

only thing we can know is that we lost one more component of human

diversity, of the versatile range of approaches and lifestyles we now

need more than ever in our search for solutions to the human

sustainability crisis, which the global mainstream of politics,

economics and attitudes to the Earth have brought about. For this

sake, it is imperative that Ainu revival efforts continue.

But there's an irony. And that

is, that so many of the good things I found on this journey – the

cities more pleasant than most I've been in (and I speak as a person

not fond of cities), the bountiful farms, the Bon Festival, and above

all the great friends I made there – all these things, descend

through history from the Japanese settlement of Hokkaido. Unique

settings, unique characters, unique culture: a journey in its own

right, of contents and chapters totally distinct from all others,

even in Japan itself.

And it would be unfair, of

course, to hold all the good people who live in Hokkaido now to

account for the things their ancestors, and their ancestors'

governments, did to the Ainu. The good things there now cannot

justify the past; equally the bloodstained past does not invalidate

the good things in the present. The crimes of the father do not

extend to the child; a certain god made the mistake of ruling that

they do (even when the crimes were not crimes at all), with

spectacular and ruinous results for humanity's ethics. Let us not

make that error again.

So what do we do? What next for

Hokkaido? The Historical Museum of Hokkaido leaves this question to

all of us; rather than answer, it offers a thought-provoking

patchwork of music and images to help us reflect. It was encouraging,

and important, to find a significant Ainu presence among these

visions of the future.

Perhaps what's important now is

to learn. We must take heart from the good things, learn how they

grew: Hokkaido's transformation in the space of 150 years, and across

the decades within that, may hold hope and tangible lessons for those

in other parts of the world where strife and poverty crush spirits,

and where transformation is desperately dreamt of. But at the same

time we must never forget, and never excuse, the crimes committed,

the sacrifices forced on others: because only then can the damage be

repaired, and only then can we work for a world where those crimes

will never be committed again.

Thus do the north winds speak to

us all. Let's listen, and think. And if you ever get the chance, do

get on the road yourself and follow to where those voices are coming

from. You might find marvellous things for your own stories there.

Ai Chaobang, September-October

2011

Previous posts in this series:

Previous posts in this series:

No comments:

Post a Comment